Apicius: the name of his restaurant?

In Imperial Rome luxurious dinning brought fame to chefs, their popularity often exceeded that of philosophers and poets. Born about 25BC Marcus Gavius Apicius, great epicurean and gastronomist left us 10 handwritten manuscripts, printed later, such as “De Re Coquinaria” (“the kitchen manual”) filled with the essentials of cooking.

Marcus Apicius stated: “Nothing pleasant can be achieved by excluding the delights of table and bed”. With a legendary reputation for exuberant fests and a close friend of Cesar Heliogabalus, he taught eating and feeding skills in Rome. Many disciples gathered around his bed covered in roses where he shared his recipes.

His manuscripts contained the foundation of many dishes, by his creation or by perfecting existing recipes such as blood sausage, ragout, sole gratin, stew, duck with turnips, sausage of pork liver, bouillabaisse, and named after him: “paté in crust” with pork, fish and chicken. A skilled chemist, he knew covering vegetables and adding salt or honey preserved them longer, cooking with niter kept the vegetables green. He named several cakes, and excelled in creating tasty sauces, combining herbs, sweet and bitter or sweet and salty flavors matching them with robust wines. One of the first master Chefs.

My dad’s cooking journey

Although he never followed a formal education in cooking, he learned the classic cuisine by apprenticeship and developed his unique modern cuisine and philosophy over the years. Started at age 14 working in the kitchen, his curiosity and search for perfection was sparked. Born without nationality in 1948 in Waasmunster, Belgium from a Flemish mother and Polish father, who died when he was 11, he obtained the Belgian nationality but never lost his Slavic roots.

Dad at Restaurant “Villa Lorraine”

He moved with my mom Nicole to Brussels and worked as commis at “Villa Lorraine” one of the most reputable 3 Michelin star restaurants in Belgium in 1970. His nervous disposition and go-for-it attitude made him stand out amongst the French speaking tight brigade; he was nicknamed “ le petit flamand” (the little Flemish) and often on the receiving end of pranks. He worked really long hours, had a really hard time but after his shift he tested his creations at home to escape reality. When one day Chef Camille Leurquin, didn’t show up for work, the restaurant owner Marcel Kreusch, asked him to run service for an important dinner party, it needed perfection and he delivered. In 1978 he was ayoung chef running the 3 Michelin starred kitchen and service for 3 months and in return was rewarded with apprenticeships during his summer holidays with the biggest chefs in the world such as the brothers Troisgros, Alain Senderens, Alain Chapel, the brothers Haeberlin, Michel Guérard and Frédy Girardet. This rocked his world.

Dad’s cooking philosophy

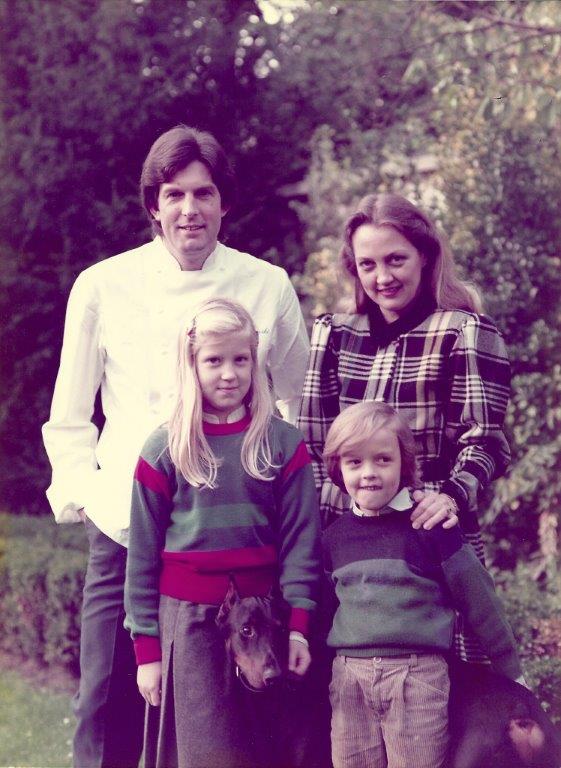

He opened his own restaurant Apicius in April 1980 fueled with many ideas and his overpowering need for perfection; many a dish was thrown out and started over again until he was satisfied. He challenged everything and everyone around him but most of all himself; extreme in all he did he searched and pushed himself often to the limit. He took up cycling and took it to the extreme; he formed friendships with many athletes such as Eddy Merckx and road until he calmed the devil in him, about 200km per week. His constant companion was his Doberman Marcus Gavius, named after the same author he named his restaurant; he needed a dog with the same passion for life. Although the name of the restaurant was tribute to one of the first roman chefs, he also cleverly ensured it was neither a French nor Dutch name. “A” starting the alphabet, he would be listed first in guides also. His creativity triumphed and threw overboard all classical roadblocks and wanted to hang up the sign: “Laboratoire de cuisine” (kitchen laboratory). He hangs out with painters and writers, buys every modern and ancient cookbook he can find, as many books on herbs and edible plants, he studies, researches and develops his philosophy of the “la Cuisine Réfléchie” (the reflective cuisine).

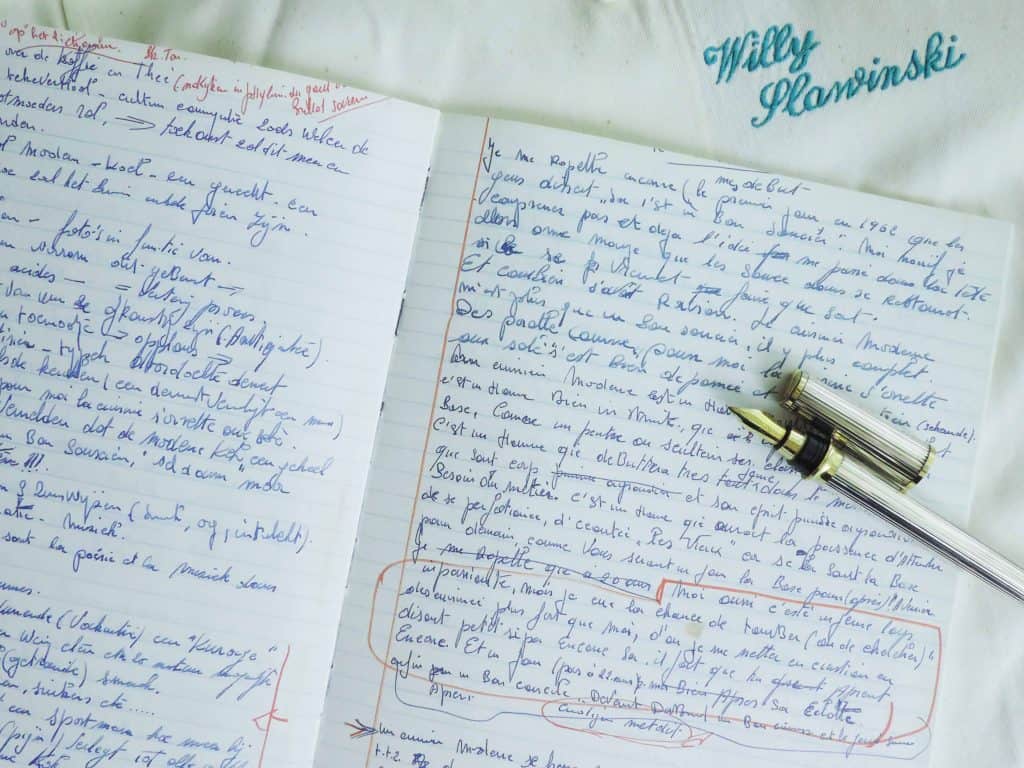

He favors steaming fish and meat, experiments with reducing cooking times, prefers serving dishes lukewarm and cold soups, uses many new vegetables (such as romanesco cauliflower ), fresh herbs (such as pimpernel, angelic and red basil), woody mushrooms (testing their toxicity himself), edible flowers (such as bourrache (starflower), calendula (marigold), capucine (nasturtium), monarda, violets, roses & zucchini blossoms) and “exotic” ingredients (such as pâte a brick), a first ever and difficult to accept by some. He created a light cuisine, packed with flavor and easily digestible. He drastically reduced use of salt and replaces it with natural aromas such as celery. Acidities in fruits such as rhubarb, nuts such almonds give a natural bitterness and the scent of mushrooms provides depth to a dish. He is groundbreaking, a pioneer of his time! He creates dishes with combinations of ingredients never tasted before such as scallops with squid ink, duck with a chocolate sauce, langoustines with salsify with vanilla, little spinach parcels with pear and chocolate sauce, tartare of pineapple and carrots with Vacherin (cheese). He called it ‘Taste and Anti-Taste”: unusual combinations that come together in a surprising harmony. He removes salt and peppershakers from his tables and challenges his customers to really taste the flavors, the ingredients and the dish. He started working on his book where he was prepared to share his idea of a healthy and gastronomical cuisine opposing the rise of “fast food” and creating dessert without sugar nor flower. His vision for the future was a delicate balance between nourishment of body and soul and by pushing the boundaries of technology, this to obtain not only a culinary experience but also an emotive experience. He passed away in 1992 before finishing his book.

In 1982 he received his first public recognition “ la Clef d’Or” de GaultMillau. In 1984 he received his first Michelin star and his second star in 1986. The relationship with Michelin was always a difficult one; he felt misunderstood and was fighting against an institution wanting to save tradition by standing in the way of innovation.

In 2007 my mother, brother and I brought out a memoire of his work, using bits and pieces of what he wrote, some recipes, friends and family share stories of him and most of all his philosophy. Homarus published 2000 numbered books in French and Dutch.